by Justin Miller | Nov 19, 2025 | Historical Theology, Practical Theology, Preaching

*Editor’s Note: This section is adapted and updated from a book by Justin Miller called John Owen’s Pastoral Preaching, published by WIPF & Stock in December 2021. Used with permission from the author.

Preaching as the Primary Ministry of a Pastor

Charles II once asked John Owen why anyone would listen to the preaching ministry of a fellow dissenting pastor in his time that was a tinker who lacked formal education, a preacher named John Bunyan. [1] John Owen is quoted as replying, “Could I possess the tinker’s abilities for preaching, please your majesty, I would gladly relinquish all my learning.”[2] It is clear from statements such as these that Owen viewed preaching as primarily something that benefited the flock of the Lord Jesus, not fueled by apocalyptic ideologies applied to his time, as he has been accused of by scholars such as Gribben. John Owen saw preaching as the primary ministry of a pastoral ministry per the Biblical commands found in Holy Scripture (John 21:15-25, Acts 20:17-31, Ephesians 4:11-15, and 2 Timothy 4:1-2). [3] Barret and Haykin state in their book on John Owen:

“John Owen (1616–1683) is widely regarded as one of the most influential English Puritans. As a pastor, he longed to see the glory of Christ take root in people’s lives. As a writer, he continues to encourage us toward discipline and communion with God.”[4]

Their analysis of Owen seems to prove true from his own writings, especially his priority of preaching being that God’s people may grow in their affections for the Lord Jesus. Owen stated in The True Nature of a Gospel Church the following:

“The first and principal duty of a pastor is to feed the flock by diligent preaching of the Word. It is a promise relating to the New Testament that God would give unto his church ‘pastors according to his own heart, which should feed them with knowledge and understanding,’ Jer. iii.15. This is by teaching or preaching the Word, and no otherwise. This feeding is the essence of the office of pastor, as unto the exercise of it; so that he who doth not, or can to, or will not feed the flock is no pastor, whatever outward call or work he may have in the church.” [5]

This statement is packed to the brim with a summation of Owen’s ideology when it comes to the preaching of the Word of God. Notice what John Owen says in the opening of this statement concerning what preaching is. He defines pastoral preaching as simply “feeding the flock of God from the Word of God.” [6] He clearly outlined the primary duty of a preaching pastor/elder is to feed the flock. The flock is pictured in need of food to sustain them in their existence. The food for sustenance of the spiritual person per Owen was the Word preached. Owen in his book The True Nature of a Gospel Church stated the following, “The care of preaching the gospel was committed to Peter, and in in him unto all true pastors of the church, under the name of “feeding, ‘John xxi. 15-17.” [7] For a flock to be properly nourished and thereby to function as designed they are to be fed nutritiously by the pastor from the proper interpretation, proclamation, and application of the Scripture. [8]

Owen made it clear that what was at stake with regards to the preaching ministry of a pastor is the very spiritual health of the flock of God. By using such language, he meant precisely what he had stated. If the flock is not be well fed, then logically, they would be malnourished at best and starved at worst. If fed inappropriate portions and non-nutritious sermons, they would not function as designed, just as a malnourished physical body would not function as designed by God. Owen conveyed on the forefront the grave importance of proper pastoral preaching. He stated about preaching, “this feeding is the essence of the office of pastor.” [9] By using the word “essence”, which means the nature of something or the most significant part of something, Owen seemingly made a very strong case and point for pastoral preaching in the life of a pastor. The very nature and most significant part of the pastor’s office per Owen was the proper preaching of the Word so that the flock of Christ may be sustained and grown spiritually. As a proper diet helps a growing child become an adult, so a proper diet of the Word in the local church helps a babe in Christ become a mature follower in Christ. He could not express that reality with more clear terms. Clearly Owen’s writing matched the teaching of Paul’s exhortation to Timothy in 2 Timothy 4:1-2 with regards to pastoral preaching.

Truth of the preached Word seen in the pastor’s life

He practices what he preaches. This phrase is held to ministers’ lives with regards to their conduct in the life of their family, the church family, and the community. Paul tells Timothy in 1 Timothy 4:16, “Pay close attention to yourself and to your teaching; persevere in these things, for as you do this you will ensure salvation both for yourself and for those who hear you.” The idea is that Timothy is to keep faithful to apostolic doctrine and his life is to match the apostolic doctrine he holds to. For the Biblical narrative, preaching is the priority for pastoral ministry as seen in 2 Timothy 4:1-2, and a testimony of the truth pastors preach must be seen in their own lives. John Owen would have agreed with this sentiment wholly. Owen believed the truth of Scripture must be a reality evident in the pastor’s own life for him to be faithful in ministry and life. If preaching were truly the pastor’s priority, his message must be seen in his everyday life increasingly. Owen wrote in Eschol, A Cluster of the Fruit of Canaan: Mutual Duties of a Church Fellowship, “If a man teach uprightly and walk crookedly, more will fall down in the night of his life than he built in the day of his doctrine.” [10] He goes on in the same book to state:

“Now, as to the completing of the exemplary life of a minister, it is required that the principle of it be that of the life of Christ in him, Gal. ii. 20, that when he hath taught others he be not himself ‘a cast away.’”[11]

John Owen, from comments such as this, as well as his demands for Christians to pursue holiness in his book, The Mortification of Sin, would likely have had great difficulty with the state of modern ministry in the Western world today.

Owen emphasized that “able to teach” (gifting) is only listed as one of many qualifications for eldership and the preaching ministry of the Word. Remember, Owen wrote, “If a man teach uprightly and walk crookedly, more will fall down in the night of his life than he built in the day of his doctrine.” [12] For Owen, gifting was not enough. A man had to practice what he preached rightly from the Word of God. As Paul tells Titus in Titus 1:15-16:

“To the pure, all things are pure; but to those who are defiled and unbelieving, nothing is pure, but both their mind and their conscience are defiled. They profess to know God, but by their deeds they deny Him, being detestable and disobedient and worthless for any good deed.”

A pastor must know God and walk with Him in order to be qualified to proclaim Him to His redeemed people.

However, that is not to say that gifting did not matter in light of the high priority of preaching. It matters greatly per 1 Timothy 3:1-5 and Titus 1. Owen emphasized this reality for the preacher. Owen highlighted the priority of a pastor’s character for the pastor to be considered and called to preach the Word. However, it would be a mistake to think he stopped just at character. He emphasized character but also combined it with competence to preach in order for a man to fill a pulpit rightly.

Cannot preach then not a pastor

A lot of times people can drift from one extreme to the next. It is always helpful to avoid such tendencies. By saying the character of the person who is seeking the office of elder matters is not saying that gifting does not matter. Gifting matters greatly as well to the glory of God! Paul in Romans 12:6-8 writes:

“ Since we have gifts that differ according to the grace given to us, each of us is to exercise them accordingly: if prophecy, according to the proportion of his faith; if service, in his serving; or he who teaches, in his teaching; or he who exhorts, in his exhortation; he who gives, with liberality; he who leads, with diligence; he who shows mercy, with cheerfulness.”

The concept Paul puts forth is that every Christian is gifted by God the Holy Spirit with abilities that are to be used for the good of the church of the Lord Jesus. Genuinely called ministers of God are therefore gifted by God for the work of feeding the flock of God. They are “able to teach” as Paul writes to Timothy about elders in 1 Timothy 3:2.

John Owen’s view of pastoral preaching, though rooted in godly character, went beyond just character qualifications to evaluating whether a man had been gifted of God for such a vital work. Paul’s admonition to Timothy about elders being able to teach seems to have stuck with Owen in his assessment of pastoral candidates. As mentioned earlier, Owen’s wrote, “Gifts make no man a minister; but all the world cannot make a minister of Christ without gifts.”[13] He demanded that pastors be able to preach if they were truly to be a pastor. [14] It was unthinkable to Owen for a man to be confirmed to a pastorate if he could not correctly expound the Scriptures every Lord’s Day just as it would have been for Paul per 1 Timothy 3:2 with “able to teach”. He stated, “this feeding is the essence of the office of pastor, as unto the exercise of it; so that he who doth not, or can to, or will not feed the flock is no pastor, whatever outward call or work he may have in the church.” [15] For Owen, in this statement, a man must be able to teach the Bible and proclaim it correctly to fill the office of a pastor, no exceptions allowed. If a pastor did not have the proper tool kit, the God given ability, and the understanding of Scripture to rightly interpret, expound and thereby proclaim the Scripture, then that person was not a true pastor no matter what a church had externally confirmed with regards to that man. The argument is something like this: a fisherman who cannot fish should not be a fisherman, an accountant who cannot count should not be an accountant, a doctor who does not know anatomy and medicine should not practice, and a pastor who knows not the Word well and cannot preach should not take a pulpit and hold the office of pastor. Every office has a function and if a person does not have the gifts to fulfill the function, they should not hold the office. The preaching elder/pastor had to be able to correctly explain the Scriptures and thereby feed the flock, for that was their function to do so in the local church. John Owen expounds further concerning the capability of a true preacher and their preaching ministry in order to protect churches from error:

“(1). A clear, sound, comprehensive knowledge of the entire doctrine of the gospel. (2) Love of the truth which they have so learned and comprehended.. (3) A conscious care and fear of giving countenance and encouragement unto novel opinions. (4) Learning and ability of mind to discern and disprove the oppositions of the adversaries of the truth. (5) The solid comprehension of the most important truths of the gospel. (6) A diligent watch over their own flocks against the craft of seducers from without, or the springing up of any bitter root of error among themselves. (7) A concurrent assistance with the elders and messengers of other churches with whom they are in communion, in the declaration of the faith they all profess.” [16]

Owen, like Paul in 1 Timothy 3:2, called for and even demanded that anyone who would climb into a pulpit had to be able to proclaim the Word of God faithfully to a congregation on the Lord’s Day, as well on any occasion. Paul in Titus 1:9 takes the ideology of being able to teach (defend and expound sound doctrine) and adds reasoning behind it with regard to the high priority of preaching. Paul states in Titus 1:9, “He must hold firm to the trustworthy word as taught, so that he may be able to give instruction in sound doctrine and also to rebuke those who contradict it.” Like Paul to Titus, Owen believed a pastor must be a man who had to have a sound understanding of the doctrine of the Gospel, love of the truth, appropriate learning, an awareness of what is threatening the flock, and a fellowship with like-minded pastors for mutual accountability in the calling therein (which is not something Paul had said directly but could be implied from unity texts such as Christ’s high priestly prayer in John 17:20-21). [17] A pastor who did not fit this criterion was one who would not be able to rightly defend the doctrines of the faith nor be able to approach the Scripture in a way that would ultimately be a benefit and help to a local gathering of God’s people. [18] Therefore, such a person was not qualified for the office of pastor per Paul’s writing and per John Owen’s understanding of all of Scripture. Owen would have seen putting pastors in pulpits who are unable to preach the Word with accuracy as a grave error because of his high emphasis on the priority of preaching. In the time of the author, in many denominations what is required of a person is that they will be willing, “feel called”, eager, and a relatively moving speaker. John Owen from his writings would likely strongly urge caution. The feeding of the flock the Word of God was such a priority to Owen that a person who endeavored to do so must be equipped to teach the Bible correctly and accurately before he should ever enter into a pulpit to preach to the precious people of God. Owen’s thinking from his writings fit the ideology we see in Paul’s writings in 1 and 2 Timothy as well as Titus.

It is helpful to also remember that Owen was at one time the Dean of Christ Church Oxford and Vice Chancellor. He had a vested interest in the equipping of young men for the ministry because of the priority of preaching. I once heard a seminary professor describe the lifelong lesson he learned from a seminary president.[19] He had made the remark to the seminary president that he did not need all this learning. He should be out preaching now without having to sit in class and wait for his time to go out into the world. The seminary president had this man carry a bucket of sand with him wherever he went. The president of this seminary reminded the young man that the Apostle Paul spent approximately 2.5 years in Arabia preparing for the ministry Christ Jesus had called him to. If Paul needed time in the Word so too did he and all students who would proclaim the Word of God. The sand was to remind this student of Paul’s time in Arabia and thereby the importance of having the tools to properly teach the Holy Scripture. John Owen, per his statements, would likely have greatly agreed with the president of the seminary because of his view of the priority of faithful pastoral preaching in the local church. A pastor must be able to preach the Word with accuracy and clarity by God’s grace. A pastor is to have the tool kit and ability to carry out this charge and task. Just as a physician must be medically trained and a lawyer versed in the fine points of the law, so too a pastor who preaches to a flock must be trained well in the Holy Scriptures and doctrine therein. What is at stake is nothing less than the souls of those in the congregation per Paul the apostle and John Owen many years after him.

A moral duty

Preaching, to John Owen, was not only the primary function of a pastor and, therefore, the highest of the pastor’s priorities, but also more than that. For Owen, it was a moral duty of the highest importance to be undertaken with the most reverence possible of one truly called of God into the pastoral office. Owen wrote that the duty of a pastor is to “declare the gospel, when called by the providence of God thereunto, for the work of preaching unto the conversion of souls being a moral duty.” [20] He believed resolutely that preaching was a moral duty of a pastor, particularly with the unconverted in mind (Emphasis mine). He understood well that the Gospel would build the sheep and call the lost sheep into the fold. Preaching for Owen thus was not only a holy charge, but an issue of great moral importance that must be adhered to with the greatest dedication. He saw the Word of God as something that gave the ordinances (the Lord’s Supper and Baptism) their authority and the Word was entrusted to the shepherds of Christ’s flock. He stated in a sermon:

“The administration of the seals of the covenant is committed unto them, as stewards of the house of Christ; for unto them the authoritative dispensation of the word is committed, whereunto the administration of the seals is annexed; for their principal end is the peculiar confirmation and application of the Word preached.” [21]

Owen is his book True Nature of a Gospel church emphasized the Word of God has been entrusted to pastors as a holy and sacred stewardship. [22] Again, per Owen it was a serious stewardship that was a moral imperative to perform faithfully. [23]

Was Owen’s view in accordance with what Scripture conveys concerning the role of a pastor being a steward of the truth? The story of Joseph, the son of Jacob in Genesis, highlights the idea of faithful stewardship well. In Genesis 39, Joseph, as a steward, managed the assets and affairs of his master, Potiphar, for the expansion of his master’s assets and household. Joseph’s story highlights that a steward is one who manages the assets of their master. In Matthew 25:14-30, Jesus expounds the truth of Biblical stewardship through the parable of the talents, whereby a master entrusted several men with a sum of talents and they were to multiply what was given to them while their master was away. Faithfulness to steward what was given to them was the criterion of evaluation upon the master’s return. For the talents belonged to the master. Two of the three servants mentioned in Christ’s parable heard the same affirmation, “Well done, my good and faithful servant”. The servant who did nothing with what the master had entrusted to him was cast away into darkness and destruction. The point was how the servants handled what had been entrusted to them showed their love (or lack thereof for the third servant) of their master. John Owen put forth that pastoral ministry, particularly pastoral preaching, is a stewardship by which men were entrusted with the Word of God to feed the flock of Christ Jesus. Therefore, it was a moral obligation that could not be neglected for true pastors.

Paul states in 1 Corinthians 9:16 a similar sentiment. Paul states in 1 Corinthians 9:16, “For if I preach the gospel, that gives me no ground for boasting. For necessity is laid upon me. Woe to me if I do not preach the gospel!” Paul connected the priority of preaching the Gospel with its necessity for a man called by God. To not do so was to be morally in error before God. Paul said “woe” to him if he did not preach. Paul in Colossians 1:25 calls his ministry a stewardship from God, which in Colossians 1:29 he labored at by God’s grace in him. Owen’s perspective of pastoral stewardship seemingly is rooted in the same ideology that we find in Pauline literature as well as the Scriptural narrative of stewardship. It was a moral duty. Owen held that pastors as stewards are to be found faithful before the Lord Jesus, the Master of the church. Like Paul, Owen saw faithful pastoral preaching for the pastor of a flock to be a moral imperative.

[1] Barret, Matthew. Michael A. G. Haykin. Owen on the Christian Life. 23.

[2] Ibid, 23.

[3] Owen, John. The True Nature of a Gospel Church. 74-75.

[4] Barrett, Matthew. Who Is John Owen? (Issue 4, Vol 5. of Credo: The Prince of Puritans: John Owen November 2015), 12.

[5] Owen, John. The True Nature of a Gospel Church. 74-75.

[6] Ibid, 74-75.

[7] Ibid, 75.

[8] Ibid, 75.

[9] Ibid, 74-75.

[10] Owen, John. Eschol, A Cluster of the Fruit of Canaan: Mutual Duties of a Church Fellowship. 57.

[11] Ibid, 57.

[12] Owen, John. Eschol, A Cluster of the Fruit of Canaan: Mutual Duties of a Church Fellowship. 57.

[13] Owen, John. Posthumous Sermons: The Ministry of Christ. 432.

[14] Owen, John. The True Nature of a Gospel Church. 75.

[15] Owen, John. The True Nature of a Gospel Church. 75. Emphasis mine. Owen viewed ability to teach the Bible as vital for ministry of a pastor to such a degree if one would not, could not properly explain/proclaim the Scriptures they were not a pastor.

[16] Owen, John. The True Nature of a Gospel Church. 82-83.

[17] Owen, John. The True Nature of a Gospel Church. 82-83.

[18] Ibid, 82-83.

[19] This is a story shared by a professor concerning his interaction with the President of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary’s at the time of his matriculation. I’m unable to find the exact message this story was shared, but this synopsis covers what the professor conveyed.

[20] Owen, John. Eschol, A Cluster of the Fruit of Canaan: Mutual Duties of a Church Fellowship.56. Emphasis mine.

[21] Owen, John. True Nature of a Gospel Church. 79.

[22] Owen, John. True Nature of a Gospel Church. 79.

[23] Owen, John. Eschol, A Cluster of the Fruit of Canaan: Mutual Duties of a Church Fellowship.56.

by Justin Miller | Nov 18, 2025 | Church History, Practical Theology, Preaching

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from William Perkins on Pastoral Theology, published by Resource in 2023, used with permission from the author.

Reading Perkins’ description of the office of pastor and its high calling, one can easily ask, “Who is capable of such a thing?” Perkins believed men entering ministry must be prepared for such a high calling. Part of Perkins’ answer to such a query would have been that a pastor must be set apart and trained. Perkins believed in a thoroughly educated clergy. In his commentary on Galatians, he outlined in detail the importance of a properly taught clergy, which was a problem that he noted for those who proceeded generations after the apostles. He writes, “For teachers themselves must first learn, and then teach.”[1] He noted that teachers of the Word must first have been taught the Word themselves. He emphasized that there were no shortcuts to proper ministry. Diligent preparation was required and vital to the faithfulness of a pastor. The language of feeling called and sent immediately to preach would have been abominable to Perkins and all the Puritans. Perkins writes:

“If every true minister must be God’s interpreter to the people, and the people’s to God, then hence we learn that everyone, who either is or intends to be a minister, must have that tongue of the learned which is spoken of in Isaiah 50:4. Here the prophet says (first, in the name of Christ, as He is the great Prophet and Teacher of His church, and, second, in the name of himself and all true prophets while the world endures), ‘The Lord God hath given me a tongue of the learned, that I should know to speak a word in season to him that is weary.’”[2]

For Perkins, an uneducated clergy would be a great harm to the Church, as she would be unable to discern the deceitful teachings and false ideologies of man (Ephesians 4:14). He understood the importance of pastors knowing their Bibles, their faith, their historical theology, and the heresies that had threatened the Church for ages. The pastor was no less than an ambassador of Christ to the people of Christ. He advocated for a model of ministry that trained pastors in a rigorous academic setting combined with accountability that promoted true piety and holiness of heart and life among the clergymen. He would have been disheartened by much of modern pastors’ lack of training in the faith and Church history as well as the antinomianism of our time.

Perkins’ thought on the minister as an ambassador of God was embraced and perpetuated in later generations, even up to the time of Lloyd-Jones in the twentieth century. Martyn Lloyd-Jones, in his book Preaching and Preachers, states this about true pastoral preaching rooted in the truth of 2 Timothy 2:15:

“Any true definition of preaching must say that man is there to deliver the message of God, a message from God to those people. If you prefer the language of Paul, he is ‘an ambassador for Christ’. That is what he is. He has been sent, he is a commissioned person, and he is standing there as the mouthpieces of God and of Christ to address these people…Preaching, in other words, is a transaction between the preacher and the listener. It does something for the soul of man, for the whole of the person, the entire man; it deals with him in a vital and radical manner.” [3]

Lloyd Jones here captures what Perkins describes in his writings as the pastor being the “angel,” the “messenger” of Christ to His people. He is not a messenger as one who receives direct revelation. He is expounding the once-and-for-all delivered message to Christ’s people and applying it to their consciences. The pastor’s preaching is to call forth from the people of God obedience to Christ in their wills and a delighting of Christ from their affections.

Pastors must know the flock they are charged to care for

Perkins believed pastors had to know their people’s life situations and needs. He must minister to those people where they are in their life, family, work, and daily trials. A pastor, according to Perkins, must know his people. He writes:

“First, to teach that it is the minister’s duty to confess, not only his own sins, but the sins of his people, and to complain of them to God. For as he is the people’s interpreter to God, he must not think it enough to put up their petitions, to unfold their wants, and to crave relief for them at God’s hand, but he must further take knowledge of the sins of his people, and make both public and private confession of them to God…And if the minister ought to know his people’s sins, then it follows, first, that it is best for a minister to be present with his people, so that he may better know them and their state.” [4]

Perkins would have rejected any model of ministry where the pastor was more of a CEO or manager of a force of volunteers to accomplish given tasks and goals. He would not have understood this idea of a pastor not knowing his people’s names and life scenarios and would have resisted large settings as entertainment centers at the worst and preaching points at the best. He, like most Puritans, believed that pastors must know their people. John Owen, influenced by Perkins’ thought here, would later write in his book True Nature of a Gospel Church:

“A prudent and diligent consideration of the state of the flock over which any man is set, as unto their strength or weaknesses, their growth or defect in knowledge (the measure of their attainments requiring either milk or strong meat), their temptations and duties, their spiritual decays or thrivings; and that not only in general, but, as near as may be, with respect unto all the individual members of the church. Without a due regard unto these things, men preach at random, uncertainly fighting, like those that beat the air. Preaching sermons not designed for the advantage of them to whom they are preached; insisting on general doctrines not levelled to the condition of the auditory; speaking what men can, without consideration of what they ought, – are things that will make men weary of preaching, when their minds are not influenced with outward advantages, as much as make others weary in hearing them.” [5]

Owen understood that the undershepherding oversight of the flock had significant ramifications for the flock’s well-being and growth, which is why the pastor must know his people. Owen lived what he wrote, as he spent his later years caring for a smaller flock. After his university career, Owen focused his time and passion on pastoring Leadenhall Chapel in London, which he pastored faithfully until he died in 1683, a few years before the Act of Toleration of 1689 went into effect. We see Owen’s heart for his own people in a letter that he wrote to them in 1680. He addressed them as “Beloved in the Lord” and then penned the following second part to his opening:

“But although I am absent from you in body, I am in mind, affection and spirit present with you, and in your assemblies; for I hope you will be found my crown and rejoicing in the day of the Lord: and my prayer for you night and day is, that you may stand fast in the whole will of God, and maintain the beginning of your confidence without wavering, firm unto the end. I know it is needless for me at this distance to write to you about what concerns you in point of duty at this season, that work being well supplied by my brother in the ministry; yet give me leave, out of my abundant affections towards you, to bring some few things to your remembrance as my weakness will permit.”[6]

He ended the letter and signed it in the following way: “Your unworthy pastor and your servant for Jesus’ sake. J. Owen.”[7] John Owen, on this issue of pastors knowing their flocks assigned by the Lord Jesus, the Chief Shepherd to whom they belong, was clear in practice and admonition. He writes:

“Let the ministers engage themselves in a special manner to watch over his flock, everyone according to his abilities, both in teaching, exhorting, and ruling, so often as occasion shall be administered, for things that contain ecclesiastical rule and church order; acting jointly and as in a classical combination, and putting forth all authority that such cases are intrusted with.” [8]

Owen saw the pastors as those who must watch over a particular flock of Christ under Christ’s rule. Perkins had stressed such an idea years before. This was revolutionary in contrast to the Roman view of clergy, who were disconnected from the people. Perkins understood that a pastor must know his flock and take the once-and-for-all delivered canon of Scripture to their consciences and present it to the eyes of their hearts. He believed that a pastors’ highest desire for the local flock of God should be to see the members of that local church be a people who strive diligently for godliness. He saw it worth the sacrifice. He writes:

“And here such ministers as have poor livings but good people, let them not faint nor be discouraged. They have more cause to bless God than to be grieved, for doubtless they are far better than those who have great livings and an evil people.” [9]

According to Perkins, a pastor must consider it a blessing to be among “good” people and not be discouraged, for that was far better than being among an ungodly group and well-paid. A flock, though small, that was godly was a crown on the head of a faithful pastor, according to Perkins. Perkins’ statements here echo the focus of the Apostle Paul in 2 Corinthians 12:14-15 when he writes:

“Here for the third time I am ready to come to you. And I will not be a burden, for I seek not what is yours but you. For children are not obligated to save up for their parents, but parents for their children. I will most gladly spend and be spent for your souls. If I love you more, am I to be loved less?”

A faithful pastor was to desire to see the flock of the Lord Jesus flourish in godliness and holiness. According to Perkins, the pastor himself was to model such behavior. Perkins writes: “Furthermore, inasmuch as ministers are interpreters, they must labor for sanctity and holiness of life.”[10] It was not okay for a pastor to preach something and then habitually live in contradiction. Such a life would harm the pastor’s ministry and undermine the message’s validity. Holiness of life was non-negotiable for Perkins. He would have urged pastors to kill heart lusts. Lewis Allen, in his helpful book for pastors written in the time of this dissertation entitled The Preacher’s Catechism, stated, concerning the heart-lusts of the pastor which drives the pastors’ fears:

“But there is a clean-hands and pure-bodies adultery that no one sees and is seldom confessed or even recognized. And that is the preacher’s heart-lust for Something Else. Something Else? It’s that congregation, that situation, that success, that appreciation (and maybe that wage) which we don’t currently have. Whether Something Else is a real person or place, or just an imagined one, a preacher’s temptation is to take his heart’s love from what God has given him and to set it on what he believes he is entitled to. We never meant to do it. But it’s happened to us, and we feel helpless. Maybe we’re willing captives of our feelings. We nurture them, and we reason that, because we have them, they must be right – and that we really must be that good at preaching to know we’re entitled to Something Else. Adultery isn’t the main sin, though: doubting God’s goodness is.” [11]

Allen captures much of what tempts pastors today. Ambition, success, etc. Allen trumpets here what Perkins did hundreds of years earlier. For Perkins, the pastor’s ambition should be holiness and faithfulness to Christ. His exhortation, by inference, to us today would be a call for pastors to be holy as the Lord is holy. To pursue holiness as an example. To kill heart-lusts. To desire Christ above all. According to his writings, this is what was behind Perkins’ life and ministry.

[1]Perkins, William. Commentary on Galatians. Vol. 2 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by Paul M. Smalley. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2015, 45.

[2]Perkins, William. Calling of the Ministry. Vol. 10 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by Joseph A. Pipa and J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2020, 208.

[3]Lloyd-Jones, Martyn. Preaching and Preachers. (London: Hodder and Stoughton. 1971), 53.

[4]Perkins, William. Calling of the Ministry. Vol. 10 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by Joseph A. Pipa and J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2020, 244-245.

[5]Owen, John. True Nature of a Gospel Church. Vol. 16. of The Works of John Owen. (ed. William H. Goold. London: The Banner of Truth Trust. 1981), 76-77.

[6] Barrett, Matthew. Michael A. G. Haykin. Owen on the Christian Life: Living for the Glory of God in Christ. Wheaton, IL: Crossway. 2015, 267.

[7] Ibid., 267.

[8]Owen, John. A Country Essay: For the Practice of Church Government. Vol. 8. of The Works of John Owen. (ed. William H. Goold. London: The Banner of Truth Trust. 1982), 51.

[9]Perkins, William. Calling of the Ministry. Vol. 10 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by Joseph A. Pipa and J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2020, 248.

[10]Ibid, 209.

[11]Allen, Lewis. The Preacher’s Catechism. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway. 2018, 146.

by Justin Miller | Nov 18, 2025 | Church History, Practical Theology, Preaching

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from William Perkins on Pastoral Theology, published by Resource in 2023, used with permission from the author.

Paul tells Timothy in 2 Timothy 2:15, “Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved, a worker who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word of truth.” He conveys that Timothy and, by inference, all pastors, are to rightly handle the Word of God. The word “rightly handling” is the Greek participle in the present tense: orthotomeō. The word means to “guide along a straight path” or “teach accurately.” Paul wanted Timothy to “do his best” to teach accurately the Word of truth. This means Timothy was to be a man who spent much time in preparation for his preaching to the people of God in Christ. Perkins, taking his cues from Paul, had much to say about what it meant to “do your best” in sermon preparation and preaching. He writes about sermon preparation, “Preparation has two parts: interpretation, and right division.” [1]

Perkins expounds on the study of Scripture in sermon preparation for the preacher in his book The Art of Prophesying. He writes:

“Hitherto has been spoken of the object of preaching. The parts thereof are two: (1) the preparation of the sermon; and (2) the promulgation (or uttering) of it… In preparation, private study is with diligence to be used….Concerning the study of divinity, take this advice. First, diligently imprint both in your mind and memory the substance of divinity described with definitions, divisions, and explications of the properties. Second, proceed to the reading of the Scriptures in this order: Using a grammatical, rhetorical, and logical analysis, and the help of the rest of the arts, read first the epistle of Paul to the Romans, after that, the Gospel of John. And then the other books of the New Testament will be easier when they are read. When all this is done, learn first the dogmatical books of the Old Testament, especially the Psalms; then the prophetical, especially Isaiah; lastly the historical, but chiefly Genesis. For it is likely the apostles and evangelists read Isaiah and the Psalms very much…Third, we must get aid out of orthodox writings, not only from the latter but also from the more ancient church…Fourth, those things, which in studying you meet with, that are necessary and worthy to be observed, you must put in your tables or common-place books, that you may always have in a readiness both old and new. Fifth, before all these things God must earnestly be sued unto by prayer, that He would bless these means, and that He would open the meaning of the Scriptures to us who are blind.” [2]

Perkins wanted the pastors he was training to study the Scriptures rightly and receive the aid of the orthodox men before them. He emphasizes the need for pastors to be men dependent on God in prayer for His grace to grant them an understanding of these things for His glory. Notice the detail in the above quotation of what the pastor was to do in the examination of certain books and their divisions. Perkins highlighted three things to employ in the study of the Word of God:

“First, we must observe the true sense and meaning of that which we hear or read. Second, we must mark what experience we had of the truth of the Word in our own persons, as in the exercises of repentance and invocation of God’s name, and in all our temptations. Third, we must consider how far forth we have been answerable to God’s Word in obedience, and wherein we have been defective by transgressions.”[3]

He called the student of the Word not only to rightly understand the passage but also to apply it personally. It was never enough proper study to understand the truth intellectually. The truth, according to Perkins, had to touch every aspect of human existence and being.

Having prepared and studied, the pastor was to deliver the message in the grace and strength of the Holy Spirit. Perkins was not in favor of using a manuscript for the sermon itself once the study was finished and the time had come for the delivery of the sermon. He writes:

“Their study has many discommodities, who do con their written sermons word for word. (1) It asks great labor. (2) He who through fear does stumble at one word, does both trouble the congregation and confound his memory. (3) Pronunciation, action, and the holy motions of affections are hindered, because the mind is wholly bent on this, to wit, that the memory fainting now under her burden may not fail.” [4]

What had been studied and examined was to be attended to by the people of God.

The responsibility of the people to listen

In his work Three Books on Case of Conscience, Perkins outlined in Book 2, chapter 7, the necessity of the church to listen actively to biblical preaching. He writes in the opening of the chapter a question and answer to put forth his thesis:

“How may any man profitably, to his own comfort and salvation, hear the Word of God? The necessity of this question appears by that special caveat, given by our Savior Christ: ‘Take heed how ye hear’ (Luke 8:18). Answer. To the profitable hearing of God’s Word, three things are required: (1) preparation before we hear; (2) a right disposition in hearing; and (3) duties to be practiced afterward.” [5]

The people of God were also responsible for hearing the prepared and prayed-for sermon from the minister. They were to make sure they were in a posture to receive and heed the fruit of the labor of the pastor’s study. They were to prepare to hear God’s Word, ensure they had the right heart posture to hear God’s Word, and were to be diligent in practicing what they learned.

He describes several conditions of those who attend the sermon. He writes, “Unbelievers who are both ignorant and unteachable…Some are teachable but ignorant… Some have knowledge, but are not yet humbled….Some are humbled…Some do believe…Some are fallen…There is a mingled people.”[6] Perkins desired to address each one. For the hardened, that they would hear the Law; for the afflicted, that the Gospel balm would be applied to them.[7] He was concerned for the England of his time and its lack of diligent adherence to the preached Word. He writes in An Exhortation to Repentance:

“First, the gospel has been preached these thirty-five years, and is daily more and more, so that the light thereof never shone more gloriously since the primitive church. Yet, for all this, there is a general ignorance, general of all people, general of all points, yea, as though there were no preaching at all. Yea, when popery was newly banished, there was more knowledge in many than is now in the body of our nation. And the more it is preached, the more ignorant are many, the more blind, and the more hardened. So they, the more they hear the gospel, the less they esteem it and the more they condemn it. And the more God calls, the deafer they are. And the more they are commanded, the more they disobey. We preachers may cry till our lungs fly out or be spent within us, and men are moved no more than stones. Oh alas, what is this, or what can this be, but a fearful sign of destruction? Will any man endure always to be mocked? Then how long has God been mocked? Will any man endure to stand knocking continually? If then God has stood knocking at our hearts thirty-five years, is it not now time to be gone unless we openly presently?” [8]

Perkins decried much of the response of his time and the ignorance that still existed, in his time, of the Scriptures and doctrinal truth. He decried the hardness and rejection of the truth by many. Perkins had a high view of the Word of God and its place in all people’s lives. He writes:

“And so every child of God (high or low) ought daily and continually to meditate in the Word of God. But, alas, this duty is little known and less practiced. Men are so far from meditating in God’s Word that they are ignorant of it. Among many families you shall scarcely find the book of God, and such as have it (for the most part) do little use it. The statutes of the land are by very many searched out diligently, but in the meantime the statutes of the Lord are little regarded.” [9]

His pastoral heart bleeds through these statements, which also inform his view of how a pastor would be treated if he faithfully preached the Word of God.

Perkins writes about what pastors can expect as they preach the Word: “Ministers of the Word must learn hence not to be troubled if they be hated and persecuted of men. For this befell the holy prophets of God, and that in the city of Jerusalem.”[10] He understood well that faithful preaching would lead to slander and opposition from many quarters of the world. His statement flows from the reality of our Lord Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 5:11-12: “Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you.” Perkins understood that the preacher had an opportunity to live out this admonition of Christ and be slandered and persecuted as the prophets of old were for preaching the Word of God. We see Perkins’ thought further expressed by later Puritans like John Bunyan, who, in his catechism, writes:

“‘When do I sin against preaching the Word?’ ‘When you refuse to hear God’s ministers, or hearing them, refuse to follow their wholesome doctrine.’ ‘When else do I sin against preaching of the Word?’ ‘When you mock, or despise, or reproach the ministers; also when you raise lies and scandals of them, or receive such lies or scandals raised; you then also sin against the preaching of the Word, when you persecute them that preach it, or are secretly glad to see them so used.’” [11]

Bunyan saw refusing to hear preaching, and mocking the minister as a grievous sin against God, yet acknowledged its reality, as did Perkins. Yet as the pastor endured in preaching the Word of God, it was, once again, a blessed calling to be used as an instrument of God for the salvation of sinners in Christ. He believed that preaching brought men to Christ, subject to the Word of God. He knew the Christian life under the Word preached would be a life of growth in knowledge and sanctification. He writes in his work A Grain of Mustard Seed, “He who has begun to subject himself to Christ and His Word, though as yet he is ignorant in most parts of religion, yet if he has a care to increase in knowledge and to practice that which he knows, he is accepted of God as a true believer.”[12] The pastor was to preach to cultivate such an increase in knowledge and obedience. For Perkins, there was no more sacred duty or higher calling than the preaching of the Word of God to God’s people each Lord’s Day for the glory of God. Faith comes by hearing and hearing by the Word of Christ (Romans 10:17). This faith that God brings forth is the result of His blessing of the faithful exposition of the Word of God: To present Christ to the consciences of sinners in need of forgiveness and grace. To convey the Law to hearts hardened in sin. To teach the people of God the implications of faith in the Gospel for their putting off of sin (Ephesians 4:20-24).

Perkins rightly saw the pastoral preaching of the Word of God to a congregation as a sacred calling and a glorious task. Therefore, we must ask ourselves a few questions: Do we share in his high view of preaching as being the means God uses to draw His people, grow His people, and drive out the wolf? Are we willing to labor to such an end and to be poured out to see the people of God come forth, grow, and the false teacher driven away? Do we hold preaching with such a view, and can our actions substantiate our claims? By God’s grace, may we answer and live out a “yes” to all the questions posed.

[1]Perkins, William. The Art of Prophesying. Vol. 10 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by Joseph A. Pipa and J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2020, 303.

[2]Perkins, William. The Art of Prophesying. Vol. 10 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by Joseph A. Pipa and J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2020, 301-302.

[3]Perkins, William. Man’s Imagination. Vol. 9 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2020, 245.

[4]Perkins, William. The Art of Prophesying. Vol. 10 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by Joseph A. Pipa and J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2020, 348.

[5]Perkins, William. Three Books on Conscience. Vol. 8 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2019, 271.

[6]Perkins, William. The Art of Prophesying. Vol. 10 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by Joseph A. Pipa and J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2020, 335-342.

[7]Summarized from Perkins’ teaching on application of truth in sermon found in: Perkins, William. The Art of Prophesying. Vol. 10 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by Joseph A. Pipa and J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2020, 343.

[8]Perkins, William. An Exhortation to Repentance. Vol. 9 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2020, 114-115.

[9]Perkins, William. Man’s Imagination. Vol. 9 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2020, 245.

[10]Perkins, William. A Treatise on God’s Free Grace and Man’s Free Will. Vol. 6 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by Joel R. Beeke and Greg A. Salazar. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2018, 156.

[11]Bunyan, John. Instruction for the Ignorant. The Works of John Bunyan. Volume 2. Banner of Truth. Carlisle, Pennsylvania. 2021, 679.

[12]Perkins, William. A Grain of Mustard Seed. Vol. 8 of The Works of William Perkins. Edited by J. Stephen Yuille. General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Derek W.H. Thomas. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Reformation Heritage Books. 2019, 653.

by Jared Ebert | Nov 18, 2025 | New Testament, Old Testament, Practical Theology

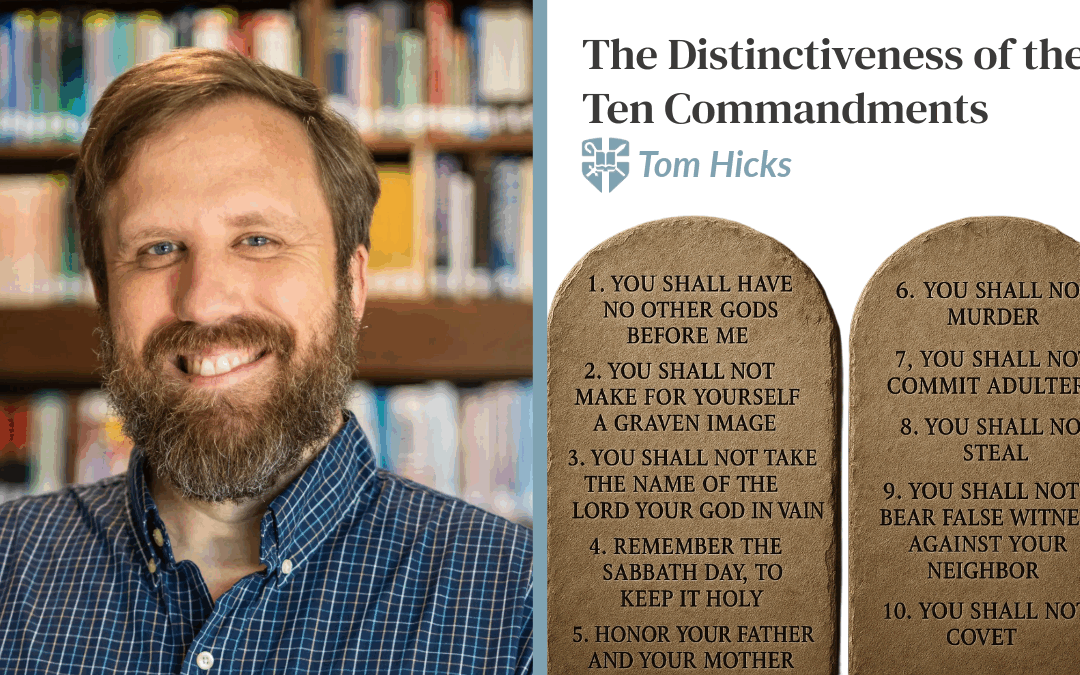

The translation of Scripture is an ancient practice. Early on the Jews translated their Hebrew and Aramaic into Greek. Shortly after Christ the New Testament is brought into various languages like Coptic, Ethiopic, Syriac, and Latin.[1] Bringing the Bible into the vernacular became a uniquely Protestant task in the Reformation, and we still enjoy those fruits today. However, if you stopped and asked many congregants in the western world, “Why do we have an English Bible?” Or “Could you tell me, from Scripture, why we should care about Bible translation?” I suspect that many would not have a thought through answer. Since we have enjoyed the benefits of the Bible in our mother tongue, and we are not actively having to defend this privilege, we do not think through the question. With this issue in mind, I want to present to you William Tyndale’s reasons for translating the Bible. There will be three sections to this article. First, I want to set the historical scene, so that you might better understand the English-speaking world in Tyndale’s day. Second, I want to summarize the five reasons for Bible translation that Tyndale gives. Finally, I want to call you to action with some reflections and applications for our own day.

The Historical Setting

When William Tyndale was born in Gloucestershire in 1494 the idea of an English Bible was not far off. John Wycliffe (1320–1384) had led a group of Christians who would become known as Lollards, and they had the English Bible, translated from the Latin vulgate.[2] When Wycliffe died in 1384 the Roman Catholic Church responded with the Synod of Oxford, which published a declaration in 1408.[3] This statement declared that it was illegal to translate the Bible into English unless it was commissioned and authorized by the Pope and his Bishops.

Because of this, translation of the Bible into English remained illegal until after Tyndale’s death in 1536. Nevertheless, there were men, prior to Tyndale, calling for a vernacular English Bible. John Trevisa (1342–1402) defended this effort in two particularly important publications. These found their way into Tyndale’s hands when he was a young boy, and he would go on to cite one of them in his later theological works.[4]

Desiderius Erasmus, a Roman Catholic humanist, was also a loud voice advocating for the Bible in the common language. In fact, this priest had the audacity to write things like,

Christ wishes his mysteries to be published as widely as possible. I would wish even all women to read the gospel and the epistle of St. Paul, and I wish that they were translated into all languages of all Christian people, that they might be read and known, not merely by the Scotish and the Irish, but even by the Turks and the Saracens. I wish that the husbandman may sing parts of them at his pillow, that the weaver may warble them at his shuttle, that the traveller may with their narratives beguile the weariness of the way.[5] [Emphasis added]

Two details are noteworthy about this Erasmus quote. First, this is found in Erasmus’ Enchiridion, which was the first work which Tyndale ever translated into English.[6] Second, Tyndale seems to be echoing Erasmus when he says to that Bishop in Sir John Walsh’s home, “I defy the pope and all his laws. . . If God spare my life, ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth the plough, to know more Scriptures than you do!”[7] As you can see, when Tyndale comes on the scene, the Lord had been stirring the waters in the English-speaking world for a long time.

If you were an average congregant in England in those days, the whole church service would have been in Latin, except for the English “curses.” You would also have likely seen the burning of Lollards who were found in possession of pieces of the Bible in English. For instance, on April 4, 1519, six men and one woman were brought up on charges for teaching their children the Lord’s Prayer in English. As they released the woman from prison, a scroll rattled in her sleeve which was the Lord’s Prayer, Apostles’ Creed, and the Ten Commandments in English. For this they were all burned together.[8] And it is into this world that William Tyndale is called by God to work, and he knew the costs.[9]

Why Translate the Bible?

In The Obedience of a Christian Man (1528), by far Tyndale’s most important theological work, he writes to those who suffer because they want to read the Bible for the good of their souls. In the preface he is attempting to encourage them so that they are not discouraged, but that they might realize, “forasmuch as thou art sure, and hast an evident token through such persecution, that it is the true word of God; which word is ever hated in the world, neither was ever without persecution, neither can be, no more than the sun can be without his light.”[10] A large portion of this preface is dedicated to his five reasons why “the Scripture ought to be in the mother tongue.”[11] We will rehearse each of these in turn.[12]

- “God gave the children of Israel a law by the hand of Moses in their mother tongue; and all the prophets wrote in their mother tongue, and all the psalms were in the mother tongue.” God has set the first pattern, ensuring that those recipients of the Old Testament were able to hear and understand. Tyndale cites Deuteronomy 6:4-9 from his own translation. The logic is sound—“How can we whet God’s rod upon our children and household, when we are violently kept from it and know it not?” Certainly, God did not give the Law, Prophets, and Writings so that they would never be understood. He gave them to be read, taught, and obeyed.

- We have all through the Bible, commands to search the Scriptures, as well as examples of men who examined by God’s revelation. Tyndale appeals to the Bereans in Acts 17. “How can I,” asks Tyndale, “your interpretation be the right sense, or whether thou jugglest, and drawest the scripture violently unto they carnal and fleshly purpose; or whether thou be about to teach me, or to deceive me?” In order to test any teacher, or to search the Scriptures, I must have access to them in a language that I can understand.

- The sermons that we read in the book of Acts (i.e. 2:14–36, 3:12–26, 7:2–53) are all “preached in the mother tongue.” When Tyndale translates the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:5–12) he is careful to show the reader that Luke uses the phrase “his own tongue” three times (2:6, 8, 11).[13] If the Apostles preached in for the crowds to understand, Pastors in 2025 should do likewise.

- We should translate for the love of souls. Tyndale alleges that the Roman clergy does not love your soul. The proof for this fact is that they will translate all kinds of works like “Robin Hood, and Bevis of Hampton, Hercules, Hector and Troilus, with a thousand histories and fables of love and wantonness,” but they will not give you what is best for your immortal soul—the Scriptures and the Gospel. He says, “[T]hat this threatening and forbidding the lay people to read the scripture is not for the love of your souls (which they care for as the fox doth for the geese), is evident, and clearer than the sun.” Do you love the souls of those who are near you or who are lost? Then we must give them the Scriptures for them to understand!

- The last reason Tyndale gives is, that even other Roman Catholics want to translate the Bible! He cites especially Erasmus’ Paraphrase of Matthew. Most likely he has in mind quotes like, “Indeed, if I had my way, the farmer, the smith, the stone-cutter will read him, prostitutes and pimps will read him, even the Turks will read him. If Christ did not keep these away from his spoken words, I will not keep them away from his written words.”[14]

A Call to Action

The great goal of missions is to see innumerable saints before the throne and the Lamb singing their new song, “You are worthy to take the scroll, and to open its seals; for you were slain and have redeemed us to God by Your blood out of every tribe and tongue and people and nation” (NKJV). In order for these tongues to sing His praise, they must hear His name. And how will they hear without a preacher? And how will the preacher reach them unless they can be understood? In our day there are approximately 7,359 languages on this planet. The current statistic shows that only 687 of those languages have a whole Bible.[15] Friends, we need Bible translators. We need seminaries who will train Bible translators in the Biblical languages, linguistics, exegesis, and orthodox theology. And we need churches who will raise up and send Bible translators into the nations. Let us not simply enjoy the benefits and privileges of our English Bibles, but send, support, and go to bring the Scriptures to the nations.

[1] If the reader is interested in a full history of Bible translation I would recommend that they see Flora Ross Amos, Early Theories of Translation (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1920); Paul D. Wegner, The Journey from Texts to Translations: The Origins and Development of the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 1999); Bruce M. Metzger, The Bible in Translation: Ancient and English Versions (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2001).

[2] William Tyndale himself was thoroughly influenced by the Lollards and their teaching. In fact, there is some evidence that his family had a deep sympathy with the Lollards. For a thorough examination of this topic see Donald Dean Smeeton, Lollard Themes in the Reformation Theology of William Tyndale, Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies VI (Kirksville, MO: Sixteenth Century Journal Publishers, 1986).

[3] You can read a full transcript of their declaration here: https://www.bible-researcher.com/arundel.html

[4] Ralph Werrell has suggested several ways that perhaps even Trevisa’s translation style is echoed in Tyndale. Ralph S. Werrell, The Roots of William Tyndale’s Theology (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co, 2013), 27–47. In his work Obedience of a Christian Man, Tyndale explicitly refers to Trevisa when he says, ““Yea, and except my memory fail me, and that I have forgotten what I read when I was a child, thou shalt find in the English chronicle, how that king Adelstone caused the Holy Scripture to be translated into the tongue that then was in England, and how the prelates exhorted him thereto.” William Tyndale, The Works of William Tyndale, 2 vols. (Carlisle: Banner of Truth Trust, 2010), 1:149.

[5] As cited in David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 67.

[6] Tyndale translated this after returning to Gloucestershire from Cambridge in 1521 while living in the house of Sir John Walsh known as “Little Sodbury Manor.” Walsh appears to have had some “Reformation sympathies.” Thus, this would have made a safe place for the Lutheran leaning Tyndale to live, work, and teach. Smeeton, Lollard Themes in the Reformation Theology of William Tyndale, 51.

[7] John Foxe, The Acts and Monuments of John Foxe, ed. Stephen Reed Cattley (London: R. B. Seeley and W. Burnside, 1830), V:117.

[8] Timothy George, Theology of the Reformers, 25th Anniversary Edition. (Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing, 2013), 329–30.

[9] Now, we should be careful here. Tyndale was not condemned to be burned because he translated, but because of his anti-papist doctrine. Nevertheless, I do not think Tyndale made a distinction between his theology and translation. The latter flowed out of the former. He knew well the costs. I have no doubt that he was well aware of the risk and his possible fate when he wrote, “’They will kill us then,’ sayest thou. Therefore, I say, is a Christian called to suffer even the bitter death for his hope’s sake, and because he will do no evil.” Tyndale, The Works of William Tyndale, 1:332.

[10] Tyndale, The Works of William Tyndale, 1:131.

[11] Tyndale, The Works of William Tyndale, 1:144.

[12] I will not cite every individual page number. The reader can go see Tyndale, The Works of William Tyndale, 142–62.

[13] His translation of that paragraph reads, “And there were dwelling at Jerusalem Jews devout men which were of all nations under heaven. 6 When this was noised about the multitude came together and were astounded because that every man heard them speak his own tongue. 7 They wondered all and marveled saying among themselves: Behold are not all these which speak of Galilee? 8 And how hear we every man his own tongue wherein we were born? 9 Parthians Medes and Elamites and the inhabiters of Mesopotamia of Jury and of Cappadocia of Ponthus and Asia 10 Phrygia Pamphylia and of Egypt and of the parties of Libia which is beside Syrene and strangers of Rome Jews and converts 11 Greeks and Arabians: we have heard them speak with our own tongues the great works of God.”

[14] Desiderius Erasmus, Paraphrase on Matthew, Collected Works of Erasmus (University of Toronto Press: Toronto, 2008), 22.

[15] These numbers come from Missio Nexas and Progress.Bible. The full numbers are published in an article that I was privileged to publish in “The Acts 14 Report” put out by Disciple the Nations. My article is Bible Translation and the Church, 7–10, https://issuu.com/disciplethenations/docs/acts_14_report_issue_no?utm_medium=referral&utm_source=disciplethenations.org

by Tom Hicks | Nov 17, 2025 | Law, Old Testament, Systematic Theology

Are believers in Christ required to obey any part of Old Testament law, or is all Old Testament law abolished? Some theologies insist the Old Testament law is one and that the Bible never acknowledges any division among Old Testament law. I offer the following critique that perpsective. Scripture teaches that there is a division of Old Testament law: the Ten Commandments are a summary of eternal moral law, which is to be observed at all times, while other laws are positive (posited by God), binding only in the covenants in which they were given.

Old Testament

- Old Testament laws are divided into categories. Deuteronomy 4:13-14 says, “And he declared to you his covenant, which he commanded you to perform, that is, the Ten Commandments, and he wrote them on two tablets of stone. And the LORD commanded me at that time to teach you statutes and rules, that you might do them in the land you are going to possess.” Notice that the “Ten Commandments” (lit. ten words) are distinct from the other designations of Old Testament law: “statutes” and “rules.” Similarly, Moses writes, “Now this is the commandment, the statutes, and the rules that the LORD your God commanded me to teach you” (Deut 6:1). These three kinds of laws: commandments, statutes, and rules, overlap in their semantic range, but they are not identical. Commandments (mitsvah) are “codes of law;” statutes (hoq) are “ordinances;” rules (mishpat) are “case laws.” Therefore, it’s far from correct to say the Old Testament does not divide its laws into various categories. Furthermore, the order in which God gave the law in the book of Exodus implies the distinctivenesss of the Ten Commandments. God gave the Ten Commandments in Exodus 20. Then in Exodus 21-23, God reveals the civil laws. And then beginning in Exodus 25, God provides the ceremonial laws about the tabernacle. Thus, the Ten Commandments stand alone in the Old Testament as distinct and primary, while all other laws in the Old Covenant are subsequent to them.

- The Ten Commandments were revealed in a unique way. God gave the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai with loud thunder, flashes of lightning, a thick cloud, and a “very loud trumpet blast” (Ex 19:16). No other laws were revealed this way. It was a striking and emotional experience for those who were there. God wanted it to be memorable. He intended the Ten Commandments to stand out in the minds of His people above all other laws. He wanted to impact their senses so that they would never forget the distinctive importance of these ten words. Furthermore, only the Ten Commandments were spoken by God to the whole congregation (Deut 4:12-13). The other commands were spoken through Moses.

- God wrote the Ten Commandments with His own finger. Exodus 31:18 says God gave Moses “tablets of stone, written with the finger of God.” The other laws were written by the pen of Moses. The Ten Commandments were engraved on “stone” to communicate that they are fixed and permanent. God wrote the rest of the old covenant laws through Moses on paper.

- The Ten Commandments are uniquely sufficient among all Old Testament laws. The Old Testament tells us that the Ten Commandments were a sufficient summary of God’s most central laws. We see this taught in Deuteronomy 5:22, which says that after God had spoken the Ten Commandments, “he added no more.” After God gave the Ten Commandments, there was no need to add any more. The Ten Commandments sufficiently summarized the way God’s people were to express their love to Him and to one another. If God’s people obeyed these laws, then they would be keeping the heart of the law, and all other obedience would follow from it.

- The Ten Commandments alone were placed in the Ark of the Covenant. God told Moses to put the Ten Commandments inside the ark of the covenant, but to “Take this Book of the Law and put it by the side of the ark of the covenant” (Deut 31:24-26). This shows how the Ten Commandments are at the heart of all the other Old Testament commandments. The civil and ceremonial laws were only to be kept in the land of Canaan (Deut 5:30-33), but the Ten Commandments were written on the hearts of OT believers, and were kept wherever the people went (Ps 37:31; 40:8; Is 51:7).

New Testament

The New Testament also makes distinctions among Old Testament laws. While it teaches that some Old Testament laws are abrogated, it shows that others are perpetually binding on the hearts and lives of believers.

- Jesus teaches that the Ten Commandments are never to be abolished. He said, “For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not a dot will pass from the Law” (Matt 5:17). What law is Christ speaking about? He goes on to list laws from the Ten Commandments: do not murder (Matt 5:21-26); do not commit adultery (Matt 5:27-32); do not lie (Matt 5:33-37).

- Adam, the first Gentile, had the Ten Commandments written on his heart. Romans 2:14-15 says, “For when the Gentiles who do not have the law, by nature, do what the law requires, they are a law to themselves, even though they do not have the law. They show that the work of the law is written on their hearts, while their conscience also bears witness.” What law was Paul writing about? Just a few verses later, Paul goes on to list some of the Ten Commandments: do not steal (Rom 2:21), do not commit adultery (Rom 2:22), do not commit idolatry (Rom 2:22). This same law is written on the consciences of all who bear the image of God. Ephesians 4:24 explicitly links being made in God’s “likeness” to “righteousness,” which means “lawfulness.” This shows us that there is a natural law within a man, summarized by the Ten Commandments. Other laws are coventantal or positive (posited) laws, which come from outside of a man. For example, Abraham knew by nature, from within, not to murder, but he did not know to be circumcised from within. God had to reveal the command to be circumcised by covenant from without in the Abrahamic covenant. Natural law, written on the human heart, cuts across all covenants. But covenantal positive laws change with the covenant.

- Paul says one can “keep the law” without obeying the command to be circumcised. Many argue that the Old Testament law can’t be divided. But if that were true, then it would be impossible to keep the law without also keeping the command to be circumcised. Paul writes, “So, if a man who is uncircumcised keeps the precepts of the law, will not his uncircumcision be regarded as circumcision?” (Rom 2:26). Paul has a category for Gentiles who “keep the law” without obeying the Old Testament command to be circumcised. What law is Paul thinking about? Again, context shows, it’s the Ten Commandments (Rom 2:21-23).

- Paul distinguishes between “the law of commandments” and its “ordinances.”Ephesians 2:15 says that when Christ died, He abolished “the law of commandments expressed in ordinances.” Notice that Christ didn’t abolish the law of commandments itself, only its expression in ordinances. “Ordinances” are the national “rules” or “decrees” of Israel that were based on moral law, but not identical to it.

- In the new covenant, certain Old Testament “law” is written on our hearts. God blesses His new covenant people saying, “I will put my laws into their minds and write them on their hearts” (Heb 8:10). That’s a quotation from Jeremiah 31, in which the author had Old Testament law in mind. Literally, the words “write them” mean “carve them,” calling to mind how God carved the Ten Commandments into tablets of stone. While the whole Old Covenant has been abrogated in Christ (Heb 8:13), the moral law of the Old Covenant, the Ten Commandments, are written on the hearts of believers (2 Cor 3:3). Old Testament ceremonial laws relating to priesthood are abolished: “When there is a change in the priesthood, there is necessarily a change in the law as well,” but the moral law is written on the hearts of the members of the new covenant: “I will put my laws into their minds and write them on their hearts” (Heb 8:10).

Therefore, it seems clear from both testaments that there is a division among Old Testament laws. The Ten Commandments are unique because they are a reflection of God’s own character. Paul teaches us that the Ten Commandments are written on the consciences of Gentiles. They were given by God in a unique way and stand above all other ordinances. In Christ’s death, He abolished the expression of the Ten Commandments in ordinances, but He did not abolish the Ten Commandments themselves. They are written on the hearts of all members of the new covenant, which was established in His blood.